The new album from Luke Bell

Out November 7th on LP, CD and streaming

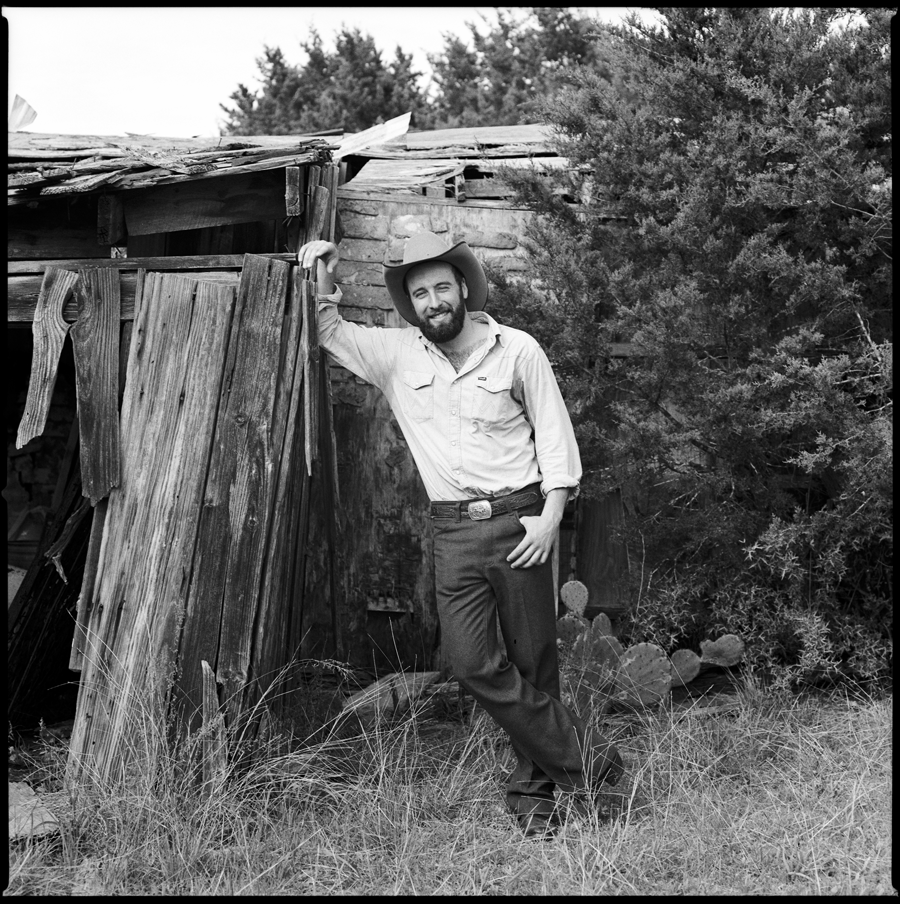

As a leader of country-western music, Luke Bell's time on the throne was short. He released one official album during his lifetime, delivering a mix of honky-tonk shuffles and Bakersfield barnburners in a voice as magnetic as his own personality. He toured briefly, graduating from career-launching gigs in the dive bars of Austin and Nashville to bucket-list shows opening for Willie Nelson and Dwight Yoakam. And then, tragically, he disappeared from the public eye to privately wage a war with the mental illness that eventually claimed his life. He was just 32 years old.

Three years after his passing, Luke's music endures. Nowhere is that more apparent than The King Is Back, a posthumous collection of studio recordings — most of them previously unreleased — that showcase his full range as a storyteller and songwriter. Tracked between November 2013 and August 2016, these 28 songs capture Luke in his artistic prime, spinning stories about blue-collar workers, heartbroken ramblers, and the personal struggles that bind us together. He'd been raised by a family of writers, and he did his part to uphold the Bell tradition, stocking his songs with characters whose bulletproof exteriors fail to hide the hurt that lurks within. Laced with pedal steel guitar, saloon-style piano, heartland hooks, and plenty of two-stepping' groove, The King Is Back isn't just a career retrospective; it's also a reminder of the timeless catalog that Bell built in three short years, pairing the vintage vibes of golden-era country music with lyrics that tackled the human condition.

Net proceeds from the album will benefit the Luke Bell Memorial Affordable Counseling Program, honoring his life by supporting mental health access for those in need. Through this release, Luke’s music continues to shine, bringing comfort, awareness, and firmly cementing Luke Bell as a legend in country music. Learn more about the Luke Bell Memorial Affordable Counseling Program below.

When I got the call on August 29th, 2022, that Luke had died, he’d been missing for over a week, and I’d been worrying. Usually when Luke disappeared, he’d check in with me or his friend Matt on a regular basis, but he hadn’t responded to any of my texts since the day after his sister’s wedding on August 20th. When I saw the Tucson number come up on my phone, I was relieved. I figured he’d been hospitalized or arrested, and that he was calling to ask for help. But when the voice on the phone asked if I was Carol Bell, if I had a son named Luke Bell, I knew he was gone.

Luke had begun noticeably spiraling into severe mental illness after his father David’s death in June of 2015, and his sisters Jane and Sarah and I had talked about Luke’s dangerous lifestyle and the likelihood of this outcome. I felt a complicated mix of emotions at first: relief that Luke’s suffering was over, sadness and even shame that I had not been able to help him, anger at our culture for its apathy about the suffering of the mentally ill, and hopelessness at the thought of a future without Luke.

Since it never occurred to me that Luke’s death would be felt by anyone other than his family and his few remaining friends, I decided to wrap up my workday before calling Luke’s sisters. Maybe a part of me understood how real his death would become once I started talking about it. I met with my last client and locked up the office, and at about 7 pm I pulled my phone out of my bag to call Jane. I felt blindsided by the avalanche of messages on my phone. Someone had sent me a link to an article about Luke’s death in Saving Country Music, and the news was everywhere. I had messages from people I’d never met. I still find the impact Luke had on his music community surprising.

Luke, however, always intended to have an impact, and he might have felt like this was a moment he’d worked hard for and earned. Since boyhood, Luke had his mind set on being heard, so he was always preparing for the day he got the mic. Once he had a clear vision for his music career, we noticed that even when he was home visiting, he practiced relentlessly and pored over YouTube videos of topnotch yodelers or harmonica players. In the early days after his death before it became completely real, I kept reaching for the phone to call him. I wanted to hear how happy he was to have all of this attention, to have him explain to me how his songs and his music added up, and to share his relief that perhaps he was finally going to be able to pay his bills without worry! It was impossible to accept that the day Luke had worked so hard for was finally here, and he was missing it.

Lucas Flitner Bell was born in 1990 to a family of music lovers, but not musicians. His family on both sides valued hard work, ambition, curiosity, education, and the idea of work as calling rather than duty. His dad’s side of the family, ending with Luke’s grandfather, included a long list of ministers and Kentucky tobacco farmers. My side of the family is made up of old Wyoming ranch families. The Bell and Flitner families shared a practical approach to life; unlike Luke, we are realists. Luke’s love of knowledge, storytelling, his charisma, work ethic, creativity, kindness, and commitment to community fit snugly into the identities of the Bell and Flitner families, but we often shook our heads with wonder at his grandiose plans for his future, his insistence on being the center of attention, and his inability to conform in order to gain the belonging he so desired.

I remember driving to town with Luke when he was in the third grade or so, on our way to his teacher’s conference. I’d already seen his report card, and it was mediocre at best. Luke was angling for an ice cream cone after his conference was over, and I wanted to prepare him for punishment (like no tv time or extra chores) based on the grim news I was braced to hear from his teacher. Usually, Luke’s teachers appreciated his curiosity and his enthusiasm but grew frustrated by his failure to complete and turn in homework and his need to be at the center of every classroom discussion. Luke interrupted me in the middle of my lecture. “Mom, why are you so worried about my grades, anyway? They KNOW I’m smart.” Though David and I did our best to encourage Luke to do better in school, he never did comply, and we found it hard to stay mad at him. He didn’t act out or rebel, he just couldn’t motivate himself to do things that weren’t interesting to him. And try as we might, we couldn’t motivate him either. And though we tried not to let on because we wanted him to succeed in a world where rule following is mandatory, he was right. We knew he was smart.

While he approached obligations that bored him with apathy, Luke tackled his interests with a single-minded passion and dedication that was contagious. Bugs, music (first as a listener and student rather than as a musician), transcendentalism, literature, ranch work, and finally songwriting and musicianship—when Luke took on these subjects, everyone in the family learned the difference between a water skipper and a water strider, or got a good book or song recommendation, or shared an afternoon on horseback riding a fence line with Luke while he showed off some project he was working on or the progress he’d made in training a new colt he’d been riding. His need for connection and shared enthusiasm when he found a new passion could sometimes be exhausting, but it was interesting and fun too. When he chose music and moved to Austin, he called almost daily to share a few lines from a song he was working on or to tell us about a new band or musician he thought we’d enjoy. Sometimes he just wanted to tell us about a friend he’d made or a person he’d met, somebody he couldn’t wait to introduce us to the next time we came to see him.

Luke had plenty of opportunity to enjoy music as a child, because his Wyoming family had a love of swing dancing and honkytonk, and his Kentucky family (raised on a strong dose of church music) loved music and dancing of all kinds. He started guitar lessons in the 7th grade when we bought him an electric guitar for Christmas. His guitar teacher, Jeff Troxel, a champion flat picker and sought after instructor, questioned me after Luke’s fourth or fifth lesson. He wondered how important it was to David and me that Luke learned classical guitar, because he said that Luke always showed up to his lessons with an agenda. He’d heard something on the radio or seen something on YouTube that he wanted to learn about. Jeff wondered if we’d feel like we were getting our money’s worth in lessons if Luke didn’t follow a traditional classical guitar student’s path. We assured Jeff of our hopes that Luke would develop a lifelong love of music; other than that, we had few expectations.

Just as Luke’s musical tastes were developing, David and I began to worry about how to keep him out of trouble in the summer. Too old for daycare, and too young to be trusted at home alone, we cooked up a plan for Luke to spend the weekdays on my family’s ranch in Shell, Wyoming, an hour’s drive east of Cody where we lived. My parents generously agreed to let Luke live in their basement, and he became a member of the Diamondtail Ranch crew and the Shell ranching community. This began Luke’s lifelong love of ranch work, as well as his interest in honkytonk music. He found a box of his granddad’s old records in their basement that first summer, and began listening to Jim Reeves and Patsy Cline, Johnny Cash, Marty Robbins, Eddy Arnold, the Kingston Trio, and Kris Kristofferson. Luke later said in an interview that he loved the stories the songs in those old records told and he also loved the way the music often encouraged people to laugh at themselves.

Luke not only found honkytonk that summer, but he also found a sense of belonging. He was a quirky kid, bent on standing out rather than fitting in. His costumes, his lack of interest in sports and Legos, his unwillingness to let others take a turn at being in charge or being the center of attention meant that sometimes the neighborhood kids left him out of their playdates. At the ranch, his quirks were annoying, but his energy and work ethic soon earned the pride of his family and the respect of the hired hands and neighborhood ranchers who worked alongside him. While Luke’s inability to take directions often got him into jams, either he or someone else would turn his antics into a funny and frequently shared story. Luke soon learned to appreciate the joy of having a starring role in a story even if the story was a comedy and the laugh was on him. His endearing ability to laugh at himself made it hard to resist his sheepish grin when he’d failed to follow directions and caused work or danger for someone else.

On one hand, Luke’s overconfidence was a sore spot for David and me, for his teachers, for his bosses, and for everyone who tried to get Luke to follow directions. On the other hand, it was his superpower. When Luke was twenty, he came home from college (where we hoped maybe he was leaning towards becoming a teacher) for Christmas break with an A in poetry but C’s and D’s in everything else, David and I decided to give him an ultimatum. If he wasn’t going to buckle down, he could pay his own bills, we told him. To our surprise, Luke announced he’d decided to drop out of college anyway. He told us he planned to move to Austin, TX, and become a musician. He said his poetry instructor, David Romtvedt, had encouraged him to put some of his poetry to music, and he’d begun playing it at open mic nights on Sunday evenings the previous semester.

At this time, we knew Luke as a mediocre guitar player and a below average singer. He had no money, little talent as far as we knew, and an old Buick Le Sabre he’d bought the summer before from an old rancher. Though we tried hard to convince him of the practicality of finishing school, Luke refused to budge from his plan. He’d already arranged to sleep on his friend Tony Browne’s couch and sell pizza coupons door to door.

Luke immediately found success as a pizza coupon salesman. He prided himself on doubling his friend Tony’s sales. He and Tony soon started a band called Fast Luke and the Lead Heavy, and Luke used his door-to-door pizza salesmanship to peddle his gigs. He soon began sending us songs he’d written and recorded on his phone. When he came home to visit that first summer, David and I overheard someone ask Luke what he was doing in Austin and we laughed at his audacity when he easily replied, “I’m a musician.” We realized he still had that Luke Bell nerve, calling himself a musician when in our minds he was a pizza coupon salesman who sometimes played a little music for beer. Still, he and Tony were only twenty-one years old, and they were having a lot of fun. We couldn’t imagine he’d ever regret giving the music business a try.

A year after he moved to Austin, Luke began talking of releasing a CD of the songs he’d been writing. He was still returning home in the summers to do ranch work, by this time on a historic ranch in Cody called the TE. He contacted a family friend and fellow music lover, Yancy Bonner, and she agreed to help him put together a Kickstarter campaign. The two of them arranged for Luke to play a gig at a beautiful historic hotel in Cody called The Chamberlin Inn. Luke’s Cody and Shell communities showed up in full force, and he easily raised all the money he needed during that evening concert. When Luke’s CD came out later that year (2012) he told Wyoming Public Radio that his favorite singer songwriters were John Prine, Townes Van Zant, Gillian Welch, Hank Snow and Johnny Cash.

One of the things we were most surprised by when we heard Luke’s songs at his Kickstarter concert was the depth of feeling in them. How does a middle-class suburban kid from Wyoming who is barely old enough to legally drink write about poverty, loss, hardship, and redemption? Luke had always had our support, but after that fundraising concert in Cody, WY, David and I stopped thinking of music as just one more of Luke’s passing fantasies, and from then on, we took his profession seriously. We knew he’d found his calling.

After his CD came out, Luke told us he was on his way to Nashville, but he planned to spend some time in New Orleans first, learning about ragtime, jazz, and a different musical culture. In New Orleans, he met many of his closest musician friends, including the members of the Deslondes and Tarek Isham. In New Orleans and through his music, he again found the belonging and kinship he’d always sought.

To pay bills in New Orleans, he worked as a roofer, and I think he wrote many of the songs on this album during that period, including the Roofer’s Blues, Blue Freightliner, and probably Hard Times. He also began to show signs of stress, worrying (sometimes it seemed obsessing) about his health. He’d already written Wolf Man and Black Crows, songs that suggest perhaps he’d experienced confusion and loss of connection with himself, and perhaps he'd already suffered episodes of psychosis and/or periods of dissociation. However, when he called with his voice full of worry, he never mentioned mental illness, and because he’d always been a person of emotional extremes, it seemed to me his unstable state of mind could be improved by abstaining from alcohol.

After that season in New Orleans, Luke came home to work on the TE Ranch for the summer, fixing fence, irrigating, and moving cattle to the high country. During these stints at home, Luke often quit drinking and smoking and started cooking healthy meals for himself in the ranch house he lived in about thirty miles up the Southfork of the Shoshone River. His work kept him fit, and he seemed healthy and happy to have time to quietly hone his musical craft while also enjoying the landscape of his childhood home. When he returned to music in the fall, he moved to Nashville. The first time David and I visited Luke there, he and his dog Bill (a stray he’d found on the side of the road during his time in New Orleans) were living in a room he rented from Bobby Bare Jr. He seemed intentional, connected, and happy. He’d quickly made friends and found his way to Santa’s Pub, which felt a lot like the Buckhorn Bar in Laramie, Wyoming where he had made his start. The first time I heard him play there, I was impressed by the sense of community, and by the warmth with which people greeted not only Luke but David and me.

Soon after arriving in Nashville, Luke recorded his second album at The Bomb Shelter with the help of Andrija Tokic. Called Don’t Mind if I Do, the album and his lyrics showed a maturity and cohesion that his first recording lacked. Luke seemed destined for success. He signed with Thirty Tigers and Big Deal Records, and he began opening for Hank Williams Jr, Dwight Yoakam (long a family favorite), and Willie Nelson. He was touring regularly with good friends and band mates Steve Daly and Carter Braillier, and he’d fallen in love with a fellow honkytonk musician named Emily Nenni.

In August of 2014, when it seemed Luke’s future could only get brighter, his dad was diagnosed with stage 4 pancreatic cancer. In a picture taken a month later, Luke and his dad are standing near a fence line Luke was rebuilding for the TE, smiling at the camera with their arms around each other’s shoulders. Luke had come home (as he often did) to earn a little extra money during a slow music season, and he looked healthy and grounded. He was twenty-four. David was determined he was going to beat the statistics, and though Sarah (my stepdaughter) and I were skeptical, Luke and Jane seemed to accept their dad’s promise when he told them somebody had to be “that guy” that beat the odds. At the time, Luke seemed without worry, and he went on to tour, write and play music, and regale us all with stories of his success. I have a picture of him at some fancy theater, grinning in front of a dressing room with his name on the door and another of him with his arm around the shoulder of Brett Dennen, a musician he knew his little sister and David and I were listening to at the time. With the backing of distribution and recording companies, he released his self-titled CD in 2015. It included about half of the tracks on Don’t Mind If I Do, as well as some new music including The Bullfighter and Where Ya Been? For the first time his false bravado seemed more like true confidence.

When Luke called to tell us he was opening for Dwight Yoakam in Charlottesville, VA, in April, I bought tickets for David and me. At the last minute, David’s cancer doctor ruled that David was too unstable to travel, so I flew alone to Virginia where my stepdaughter joined me to take David’s ticket. Luke and his band had stopped at a western store on the way into town and purchased polyester western suits in a style mimicking Yoakam’s.

I will always remember that night as one of the highlights of my life. When Luke came on stage at the Ting Pavillion, the venue seemed empty. After Luke’s first song, people started trickling down to their seats. Because we were whooping and hollering and singing all the words to his music, somebody in our row realized I was Luke’s mom, and we were soon escorted to better seats. By the time he played The King Is Back (which I was hearing for the first time) everyone at the concert was on their feet clapping and grinning. When Luke sang, “I guess you’ve all been dying to meet me, I’m sure you’ve all been wondering where I’m at,” we were all completely captivated. After the show, we met the band for a drink at a nearby bar. We stayed out past 2 am, laughing and chatting with Luke’s new “fans,” telling stories and dancing. I have a picture of Luke and me, my sister Sara, my stepdaughter Sarah, Carter and Steve lined up after the show grinning from ear to ear. Even after all of the suffering that came later, that photo still calls up feelings of pure Luke Bell joy.

In my mind, that concert was the pinnacle of Luke’s music career. His dad died two months later on June 10. Luke had been home helping with caregiving for a few weeks, and on the day of his dad’s death, he’d flown to LA for a meeting. He returned for the funeral, and he seemed quiet, withdrawn. At the funeral, the church overflowing, Luke gave me the nod at the last minute that he wanted to get up and sing. He said to the crowd, “All week, I’ve been going to sing a little gospel song I love, but as I was sitting in the pew, I could just hear my dad saying, ‘Luke, it’s not Jesus’s funeral, it’s MINE. And I want you to sing All Blue.” I felt reassured by the fact that he could still make us all laugh.

When he came home in early September to help me celebrate my birthday, he seemed anxious. He’d agreed to spend a week with my parents at their cow camp, putting in a new fence line. He was short of money, and they’d promised to pay him well. He and Emily returned to Cody only a day after they left to meet my parents—he said he’d realized he was too tired to work, and he just needed to hang out at home and rest. On an early morning hike the next day, he told me the folks at Big Deal were pushing him to release The King is Back, but he felt it was dangerous. He said he believed that if he released the song, people would think he was Jesus and try to kill him. At the time, I had no experience with severe mental illness, but I was still alarmed by his paranoia. I begged Luke to take some time off from music, or at least to check back in with his therapist in Nashville and see about getting on some anti-depressants. Looking back, though, I wasn’t as alarmed as I would be now. Luke had always been a grandiose thinker—imagining people would think he was Jesus because of a song called The King Is Back didn’t seem that far outside of Luke’s usual scope of imagination.

For the next two years, Luke was able to hide his mental illness much of the time, but the son who’d called almost every day barely checked in. When he came to Wyoming to play, he resisted playing his original music and instead played mostly covers. Looking back, I believe he was beginning to feel paranoid, worried his original music would reveal his identity to the people who were after him. He didn’t share any of this with me, though, and when he came through town with his band in the summer of 2016, it seemed he was avoiding me. He stayed with his grandparents or his aunt and uncle, or he camped out, but he wouldn’t stay with me. That fall, he was hospitalized in Nashville for the first time after a psychotic episode. For the rest of his life, he alternated between periods of stability when he lived in the mountains of North Carolina with his friend and fellow musician Matt Kinman, and periods of severe mental illness when he was hospitalized, homeless or jailed. As far as I know, he did not record any new music after 2016.

After Luke died, in a public tribute to him, one of his favorite bandmates and friends Steve Daly said in a toast on social media, “Here’s to Luke Bell. All he ever really wanted to do was create community by playing music.” Luke knew what it was like to be on the outside of community, and he went to a lot of trouble to protect others from that feeling. Many of his songs are about people pretending to be bulletproof while they are hurting and feeling lonely. Music was his way of including people and of making us feel a sense of belonging. When he played, he connected with his fellow musicians, with those of us who were listening, and we connected with each other. On stage, in the wool western wedding suit he’d found in the back of his granddad’s closet, feeling the love of all who listened, he could hardly contain his joy. I hope all of you will share that as you listen to these never-before-released tunes.

I still sometimes walk my way down the path of Luke’s life and think about some of his personality traits that might have been signs of his future severe mental illness diagnosis. He was overconfident, even arrogant, and he was a grandiose thinker. When other kids grew out of dreams of becoming famous actors or athletes, Luke’s dreams just got bigger and more outlandish. And as other kids learned to bend to fit in, Luke became more unwilling to adjust his behavior, even though he wanted more than anything to be a part of the “cool kid” crowd. And his emotions were so big: he often operated at the far ends of his large emotional bandwidth, either in extreme joy and delight or wallowing at the other end in the depths of despair. We used to joke in our family that if Luke was unhappy, everyone was unhappy, so heavy was the weight of his deep suffering.

It would be easy to leave the painful mental illness chapter out of the story of Luke’s life, except that it’s hard to know when his creative outside-the-lines thinking crossed over from quirky to unstable and even dangerous to him. But leaving mental illness out would feel like a disservice, not only to Luke, but to all of the people suffering from mental illness or from the pain of loving someone who suffers from mental illness. Luke’s way of thinking made him the boy, and later man, I loved. His songs delighted me—they showed me that he saw himself clearly, his arrogance and the vulnerability that went with it, the humor of his mistakes and flaws, often played out in the public eye. He saw himself, and he bravely shared what he saw in song. He also saw others, and he sang about that too. He sang about suffering, sweat and hard work, the loneliness that goes along with the grandeur of being “the bravest bullfighter that ever lived.” As it turns out, he also sang about mental illness, the way it felt to wake up in the morning disconnected from yourself or confused about what was real and what was imagined.

Luke’s family and I are grateful for the legacy of music he left behind. It is a reminder of his talent, his creative thinking, his suffering, his passion, and especially, his joy. Luke’s music and the friendships we have made through him allow us to stay connected to Luke even though he’s gone, and this feels like a huge gift from him. For us, though, his music has not been his biggest gift. Luke’s biggest gift to my family and me is the way that loving him helped us get comfortable with the idea that our way of seeing the world is not the only way, and his insistence on seeing it (and living it) differently has broadened and deepened our understanding of and love for the value and dignity in all of us.

Luke’s music is a testament to the fact that his state of mind was not only his curse but also his greatest gift to us. It seems unfair, even wrong, that our culture can’t make room for loving and valuing those who see the world through a lens that is different than ours and whose lens makes living a “normal” life impossible. Luke’s importance, maybe even fame, grew with his death. When he was alive and living with mental illness, he was completely forgotten, isolated, and invisible.

We hope you’ll laugh and dance it up when you hear Luke’s joyful tunes, and we hope you’ll open your hearts and minds to the suffering around you when you hear the sad ones. To be fully human is to experience both the joys and the sorrows, and to walk beside others (as Luke often did) whether they are suffering or celebrating and whether or not they see the world through the same lens as you.

In Luke's memory, his family and friends have founded the Luke Bell Memorial Affordable Counseling Program to offer financial support to those living in Wyoming's Big Horn Basin (Luke's home territory) who cannot afford mental health therapy. Follow the link below for more information about Luke or to donate. At this time, thanks to Luke's royalties and the generosity of our community, the Memorial is paying for approximately 70 therapy sessions each month and that number continues to grow.